The long, ugly history of segregated housing

The Color of Law is the sort of book that gets cited in briefs to the U.S. Supreme Court, and sometimes in court opinions themselves. Indeed, Rothstein’s book is so full of well-documented instances of government sponsored racial discrimination in the housing market that one suspects it was written with that purpose in mind.

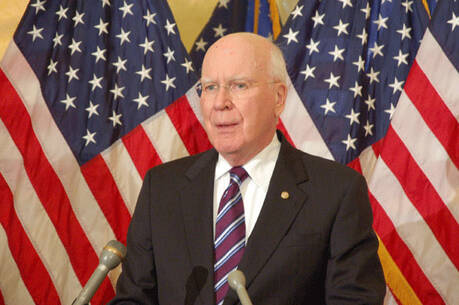

And briefs there should be, on cases yet to be brought, to overturn the U.S. Supreme Court’s stunningly obtuse decision in the 2007 case Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, 551 U.S. 701. In that case, the court struck down public school desegregation plans. In his decision, Chief Justice Roberts wrote, “Where [racial imbalance] is a product not of state action but of private choices, it does not have constitutional implications.”

Rothstein’s book takes the factual stuffing out of Roberts’s diktat. In anecdote after anecdote, fact after fact, Rothstein makes it indisputably clear that the existence of African-American housing concentrations in the poorest parts of U.S. cities and towns, served by inadequate public schools, is not a result of blacks choosing to live there, but rather, it is a result of blacks being compelled to move into these areas by government action.

One of Rothstein’s best examples is the housing patterns around the Milpitas Ford plant in central California, built to replace Ford’s Richmond plant, where there was integrated housing. This allowed many African-Americans to work there, earn a decent wage and build a middle-class life for their families. Builders developed low-cost housing tracts within an easy commute of the new Milpitas plant for white workers, with Federal Housing Administration financing available. When a Quaker group tried to find a builder to construct a racially-diverse development near the new plant, since no F.H.A. financing was available for racially integrated developments, they had a hard time finding the necessary private financing. When they eventually did, the town officials in Milpitas re-zoned the Quakers’ property from residential to industrial, making the integrated development impossible. When the Quakers found another nearby tract in Mountain View for their integrated housing development, officials there said they would never grant the necessary building permits.

When a third plot was identified in yet another town near the Milpitas plant, officials there raised the minimum lot size from 6,000 to 8,000 square feet, putting the cost of a home out of reach for working-class buyers. When the United Automobile Workers got involved and helped to find financing and a desirable plot near the Ford Milpitas plant, the Milpitas sanitary district denied it permission to connect to existing sewer lines, effectively killing the integrated development. This meant that African-American workers at the closing Richmond plant could not live anywhere near the new Milpitas plant. Those who could carpool faced long commutes from the Richmond area where blacks could live; those who took public transportation lost untold hours out of their day.

There are many Milpitas-like stories in Rothstein’s book.

The pattern is obvious. Government action left the areas around the new Ford Milpitas plant an all-white preserve and made it difficult, if not impossible, for African-Americans employed at the Richmond plant to keep their jobs at the new plant, creating cycles of poverty for these communities that have had an effect over the generations. There are many Milpitas-like stories in Rothstein’s book.

Rothstein tells how courts enforced racial covenants on residential property, of how police forces failed to protect African-American buyers in white neighborhoods from violence and how highways were routed through African-American neighborhoods near city centers to get blacks out of the way. This is all state action, not private, and it has given us the brutish situation that we have today of a nation divided into housing zones, public services and education, by skin color. So Chief Justice Roberts got it exactly wrong in the PICS case. Government action at every level has caused segregated housing and its ugly effects in the United States. How long will it take to get it right, and how long can justice wait? But when that day comes, and it will come, I am betting that the court’s decision will cite Rothstein’s The Color of Law.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Government discrimination,” in the October 2, 2017, issue.