Why do they dislike us? An American in Turkey seeks an answer.

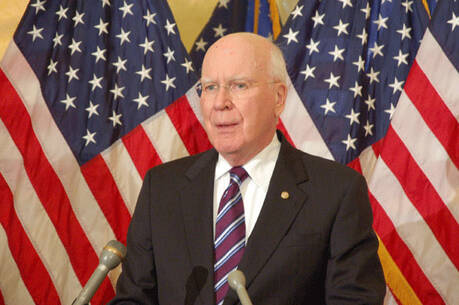

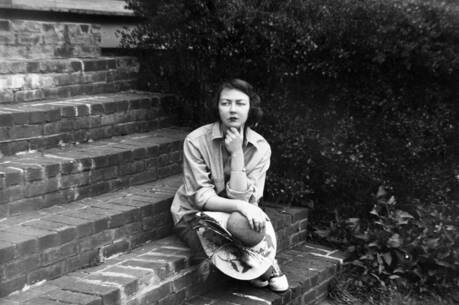

Over the past few decades, traveling abroad has become the hallmark of a certain breed of middle-class, university-educated American. As a result, travel narratives abound. But noted journalist Suzy Hansen’s Notes on a Foreign Country is not a romantic Eat Pray Love-styletale of self-discovery. Instead, she offers the sobering yet hopeful story of a young American coming to grips with the impact her country has had on the world over the past 100 years.

“For all their patriotism, Americans rarely think about how their national identities relate to their personal ones. This indifference is particular to the psychology of white Americans—who do not know that is what they are—and unique to the history of the United States,” Hansen explains in the introduction.

Hansen, who moved to Istanbul in 2007 on a Charles Crane writing fellowship and has lived there ever since, proceeds to share her growing loss of naïveté. She learns about Turkey’s nation-building as a secular state under Atatürk following the Ottoman Empire’s demise—a process that mirrors the United States’ own beginnings. She learns about the systematic U.S. effort to create a new world order after World War II: “The helpless pliancy of the Europeans and Japanese made Americans assume that the rest of the world, including Asians and Arabs emerging from their own colonial nightmares, would tolerate a new bunch of white foreigners dropping their bombs and telling them what to do.”

Suzy Hansen’s Notes on a Foreign Country is not a romantic Eat Pray Love style tale of self-discovery.

The journey that begins in Turkey continues elsewhere. Visiting Greece at the height of the global financial crisis, she learns that it was the first country in which the United States staged one of its many Cold War era interventions, covertly masterminding the murder of American journalist George Polk, pinning it on the communists and using this as a justification to provide financial and military aid to a totalitarian regime—a strategy that the U.S. government would employ again and again throughout the Cold War.

In Egypt, she learns that the United States suppressed nationalism throughout the Arab world, again for fear that it would lead to communist influence. (What it did instead was to create a power vacuum that would give rise to the Muslim Brotherhood.) She then learns that U.S. fears of communism likewise paved the way for extremism in Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Americans are sometimes surprised by the rest of the world’s dislike of them. As an American who also went abroad in this century’s first decade (first on a Fulbright scholarship to Uruguay, then to work at an international school in Nicaragua), I was ashamed at much of what I learned about my country’s long history in the hemisphere: the 1973 coup in Chile, the Contra War in Nicaragua, U.S. support of dictatorships throughout the continent, the School of the Americas. For me, Hansen’s book truly connects the dots, revealing how, at the beginning of the 20th century and especially after World War II, the United States went from rebel nation to imperial power—a move that much of the world viewed as a betrayal of its principles.

Hansen recognizes modernity as one of the most deeply rooted tacit promises of the American mind.

Hansen recognizes signs of U.S. imperialism in elements as disparate as master’s degree programs (like the University of Iowa’s prestigious M.F.A. that urged aspiring novelists to avoid history and politics when choosing their topics) and hotels (like the ubiquitous Hilton, which provides an American-style luxurious space for the world’s elite classes). She also sees a chilling correlation between American N.G.O.s, which often bring a preconceived notion of what will be best for the host country before consulting the locals, and the U.S. military.

One thread that runs through the entire book is the discussion of modernity, which Hansen recognizes as one of the most deeply rooted tacit promises of the American mind. “So much of what I read about Cold War programs has a deeply familiar ring of truth; so-called modernity trumped up as the antithesis of Islamic societies; globalization and neoliberalism accepted as natural, inevitable phenomena...deep down I had found Erdoğan’s pro-business, American-sounding rhetoric deeply comforting, the obvious path forward for Turkey.”

Hansen ultimately must face her own tacit assumptions of American exceptionalism and superiority.

For me, Hansen’s discussion of modernity recalls the work of Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor, who has set out two theories of modernity. In his “cultural theory” of modernity, “the contemporary Atlantic world is seen as one culture (or group of closely related cultures) among others, with its own specific understandings, for example, of person, nature, the good, to be contrasted to all others, including its own predecessor civilization (with which it obviously also has a lot in common).” In contrast, Taylor’s “acultural theory” is one that “describes these transformations in terms of some culture-neutral operation...that is not defined in terms of the specific cultures it carries us from and to, but is rather seen as of a type that any traditional culture could undergo.”

According to Taylor, this “acultural” approach to modernity ultimately leads those in power to project their norms and values onto the rest of the world ethnocentrically, ignoring the existence of possible alternatives (which are still very much “modern”) and forever asking the question, “Why can’t they just be like us?”

Through her travels and contact with people—whom she usually finds know much more about the United States than she knows about their countries—Hansen ultimately must face her own tacit assumptions of American exceptionalism and superiority. Though her initial response involves a certain amount of shame, she quickly moves beyond this toward curiosity about the people she encounters (demonstrated by a genuine desire to listen to them), a humble recognition that “the American dream may have come at the expense of a million other destinies” and gratitude for “the world’s unending generosity.” Written with compassion and a deep thirst for justice, this book is a must for anyone struggling to make sense of the rapidly changing times we live in—one in which, as much our nation’s leaders continue to assert themselves, American hegemony is being ever more called into question.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “Why do they dislike us? An American in Turkey seeks an answer.,” in the October 16, 2017, issue.