It has been slightly more than a week since Pope Francis said “I like to think hell is empty; I hope it is” in an interview on an Italian television program. While he made it clear that this opinion was “not a dogma of faith, but my personal thought,” it still raised eyebrows among Vatican observers. Is Pope Francis a universalist who believes that while hell is real, no one ends up there in the end?

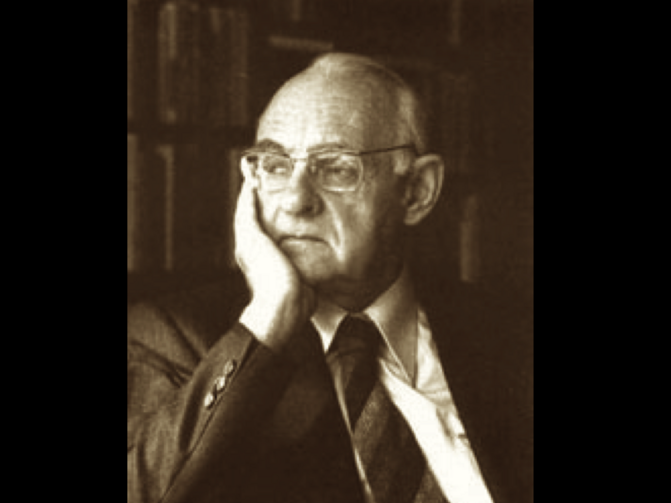

Pope Francis is not the first to raise the possibility that hell is empty, something that can sound surprising if you were taught that hell is crowded and hot and that there are probably demons setting up your particular lake of fire right now. One of the more prominent theologians of the past century, Hans Urs von Balthasar, did not deny the existence of hell but asked in a 1988 book: Dare We Hope That All Men Be Saved? His answer was a surprising one: We are probably not all saved, but it may be part of our Christian duty to hope so. Otherwise, we limit the mercy of God.

Is Pope Francis a universalist who believes that while hell is real, no one ends up there in the end?

Note, by the way, that this is exactly the theological hope expressed in “The Fatima Prayer” that so many Catholics learn with their rosary: “O My Jesus, forgive us our sins, save us from the fires of hell, lead all souls to Heaven, especially those in most need of Thy mercy.”

Of course, von Balthasar’s theological speculations on hell make up only a tiny corner of his huge corpus of work. Nor are they his only controversial writings: His use of gender complementarity concerning vocational roles within the church has also received criticism in recent years, especially as Pope Francis has seemed to embrace von Balthasar’s “understanding of the church as a masculine/feminine complementary duality.” But there was much more to him as a theologian.

The author of more than 80 books and 500 articles over the course of his life, he is often mentioned along with Karl Rahner and Bernard Lonergan (and Karl Barth on the other side of the Tiber) as the great theologians of the 20th century. (Avery Dulles would include John Courtney Murray, Chenu, Congar and de Lubac in this list.) Both Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI cited von Balthasar often, with the former naming him a cardinal in 1988 (von Balthasar died three days before the consistory).

Von Balthasar is often credited alongside some of the thinkers listed above with rescuing the church from “the desert of neo-Scholasticism” (his words) that dominated Catholic theology before the Second Vatican Council. “At first Balthasar was a rather isolated figure, with little influence on other Catholic theologians,” wrote Edward T. Oakes, S.J., in America in 2005. “He never attended the Second Vatican Council as a theological expert, for example, as many of his contemporaries had done. But since his death on June 26, 1988, his thought has become increasingly recognized for its remarkable erudition, daring innovations and solid grounding in the tradition.”

Christopher Steck: “Balthasar preferred an evocative and untidy richness over the kind of objective systematization characteristic of many great Christian thinkers."

Von Balthasar is best known for his works in systematic theology, particularly a 16-part “trilogy” comprised of three sets of texts—The Glory of the Lord (seven books), Theo-Drama (five books) and Theo-Logic (three books)—and a concluding Epilogue. But because of his eclectic interests—over the course of his career he wrote on everything from the church fathers to spiritual autobiographies to literary criticism and more (including a somewhat infamous afterword to a book on Tarot)—von Balthasar resists easy categorization as a thinker. “In method, Balthasar preferred an evocative and untidy richness over the kind of objective systematization characteristic of many great Christian thinkers,” wrote Christopher W. Steck in a 2005 essay for America. “He suggested that Christian truth is ‘symphonic,’ less a collection of positions and doctrines than an organic, dynamic and narratival display of divine love.” (Readers can click here for a recent review in America by the Rev. Robert Imbelli of a book on von Balthasar’s sacramental theology.)

Born in Lucerne, Switzerland, in 1905, von Balthasar entered the Jesuits in 1929. Ordained in 1936, he became a student chaplain in 1940 in Basel, Switzerland, where he met Adrienne von Speyr, a theologian and mystic who remained his chief writing partner until she died in 1967. Von Balthasar left the Jesuits in 1950 to devote himself to a lay consecrated institute called the Community of Saint John, which he had founded with von Speyr, though he remained a priest and eventually incardinated into a diocese. In 1969, Pope Paul VI appointed him to the International Theological Commission; in 1971, along with Ratzinger and de Lubac, he founded the international theological journal Communio. He died in Basel in 1988.

So, back to hell. What did von Balthasar really say in Dare We Hope That All Men Be Saved? He certainly didn’t deny that hell exists (nor did Pope Francis); after all, Scripture offers countless examples of the belief in hell, and three church councils affirmed the belief in damnation. The Catechism of the Catholic Church still has a pretty strict definition: “Each man receives his eternal retribution in his immortal soul at the very moment of his death, in a particular judgment that refers his life to Christ: either entrance into the blessedness of heaven—through a purification or immediately—or immediate and everlasting damnation” (1022). And what is that damnation? “The chief punishment of hell is eternal separation from God, in whom alone man can possess the life and happiness for which he was created and for which he longs” (1035).

What von Balthasar argued was that God’s grace may be so all-encompassing and powerful that even the worst among us might either repent of our sins at our death or find ourselves so overwhelmed by that grace that we simply submit to it. Rather different from the notion that God will eventually empty hell at the Second Coming (an idea advanced by some other universalists like David Bentley Hart), this belief—one motivated more by a greater recognition of the power of God’s grace than by any happy-clappy reappraisal of human depravity—has more proponents than you’d think.

For example, as Avery Dulles pointed out years ago in the pages of First Things, Pope John Paul II said something similar in 1999: “Eternal damnation remains a possibility, but we are not granted, without special divine revelation, the knowledge of whether or which human beings are effectively involved in it.”

So yes, hell exists. And no, it’s not up to you to decide who is there and why. Maybe nobody is. Except probably Judas and the cheating, good-for-nothing 2017 Houston Astros. 🔥🔥🔥

So yes, hell exists. And no, it’s not up to you to decide who is there and why.

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “The Death of Cicero,” by James Matthew Wilson. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Also, big news from the Catholic Book Club: We are reading Come Forth: The Promise of Jesus’s Greatest Miracle, by James Martin, S.J. Click here to watch a livestream with Father Martin about the book or here to sign up for our Facebook discussion group.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

Leonard Feeney, America’s only excommunicated literary editor (to date)

Happy reading!

James T. Keane