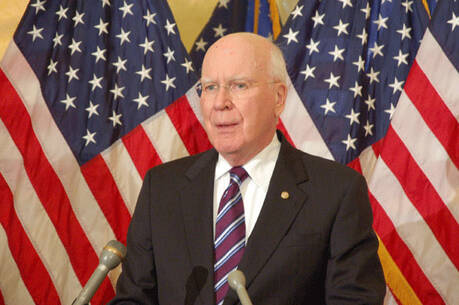

How did she lose? Bob Shrum on Hillary Clinton and the 2016 election

In contrast to Hillary Rodham Clinton’s earlier politically engineered writings, carefully combed for coming campaigns, this is a real book, written by a real person, suffused with the raw wounds of her defeat. It is marked by the bluntness and occasional tartness of someone who seems to know that her future as a candidate is past. What Happened is also marred by an apparently irrepressible instinct to accept blame and then to pass it on.

I understand the frustration. As a close adviser to Al Gore during his presidential campaign in 2000, I saw him win the popular vote, have an Electoral College majority purloined by the Supreme Court and sit just a few feet away as George W. Bush was sworn in. As a former first lady invited to Donald J. Trump’s inauguration, Hillary Clinton recalls thinking of Gore and saying to herself just before walking onto the platform: “Breathe out. Scream later.” In these pages, there is no scream, but there are engaging glimpses of how she coped with losing what many, even most, assumed was the unloseable election. “It wasn’t all yoga and breathing,” she writes. “I also drank my share of chardonnay.”

This is a real book, written by a real person, suffused with the raw wounds of her defeat.

Clinton also offers flashes of candor about “the times when [she] was deeply unsure” over the years if her marriage “could or should survive.” It did, she explains, because she always asked, “Did I still love him?” She does not need to go into the details—and thankfully she does not; we all know them.

There is often a wry sense of humor, too—for example, in her vivid descriptions of what it is like on the campaign trail: “We took eating very seriously.” She also reprises a slightly off-color piece of 1950s doggerel a friend sent her after the election:

The will of the people

Has clearly been shown.

Let's all get together;

Let bitterness pass.

I'll hug your elephant;

And you kiss my ass.

The candor has its limits. Clinton notes that she was the first first lady to participate in a gay pride parade but never reflects on the Defense of Marriage Act, signed into law by Bill Clinton, and “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” a policy he devised (both of them subsequently dismantled by President Obama). Similarly, she assails Republicans for provisions in the 1994 crime bills such as “long sentences” that ravaged a generation of young African-Americans, but she passes over her own memorable invocation at the time of the incendiary term “superpredators.”

Clinton concedes “mistakes” that were “mine and mine alone.” Well, not quite. It was a mistake to give paid speeches to groups like the investment banking firm Goldman Sachs, she writes, but everybody else gave them after they left office. It was a mistake to use private email while serving as secretary of state, but everybody did. Bill Clinton “regret[s]” the “firestorm” triggered when he climbed uninvited onto Attorney General Loretta Lynch’s plane in Phoenix at the height of the F.B.I.’s email investigation, but nothing happened beyond “exchanging pleasantries.”

Resentment is a recurring trope and is at times fully justified. She recounts her distress when NBC’s Matt Lauer, hosting a national security forum, questioned her almost exclusively about the email controversy, then let Trump glide by with questions that barely challenged his juvenile grasp of global threats and realities. Lauer was not alone: In 2016, the evening news on the major networks lavished 100 minutes of coverage on Clinton’s emails and devoted just 32 minutes to campaign-related public policy.

In 2016, the evening news lavished 100 minutes of coverage on Clinton’s emails and devoted just 32 minutes to campaign-related public policy.

Her case seems weaker, even hollow, when she assails Bernie Sanders. She allows that he hit the trail for her in the fall but implies that he had no right to run in the first place: “He didn’t get into the race to make sure a Democrat won the White House, but to disrupt the Democratic Party.” But the primaries are a contest, not a coronation. For nearly half a century, every successful non-incumbent nominee in either party has faced a vigorous and often protracted battle. The initially unheralded Sanders, an underdog who put up an unexpectedly tough fight, did enter the campaign to promote a progressive cause; but as his preparations for 2020 make clear, his aim was and is to do so not only on the stump but as president.

Another Clinton complaint is that Sanders’s pie-in-the-sky promises had “no prayer of passing Congress.” Yet her repeated attack on him was on gun control—Sanders has a few “bad votes” but a D-minus rating from the National Rifle Association—and her proposals on guns were, to put it mildly, unlikely ever to reach the floor of the House or of the Senate.

So just because something is a recrimination does not mean that it is not right. Clinton makes a powerful case, bolstered by serious social science research, that sexism was a potentially decisive driver of her defeat. (Any number of factors are sure to be decisive when a switch of only 38,000 votes in three states would have made her a clear winner in the Electoral College as well as the popular vote.) She was subjected to a brutal personal campaign from an opponent who himself is indisputably misogynistic and whose rhetoric traffics in a relentless appeal to prejudice of all stripes, on a scale unprecedented in modern U.S. history.

Clinton makes a powerful case, bolstered by serious social science research, that sexism was a potentially decisive driver of her defeat.

Clinton is also right that her campaign was hobbled by voter suppression and lacerated by “fake news” and the WikiLeaks affair—and then hurt, perhaps fatally, by F.B.I. Director James Comey’s last-minute intervention in the form of public statements that shifted the spotlight back to her emails and deepened doubts about her honesty. But the central self-analytical flaw of this book is that Clinton fails to recognize what matters in politics is not only what happens to you but what you make happen. What she did have control over in a wafer-thin election was her message and the means to deliver it.

To put it plainly, in areas of Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin that previously went for Barack Obama, she lost the message war on the economy. Yes, Trump’s claims to be on the side of working people were specious. But they were also effective. His explanations for the economic distress of those who have not shared in the post-2008 recovery were trade and immigration—scapegoats, in my view, but nonetheless a resonant message about things he said he could change that would, in turn, change their lives. Thus, while Clinton characterizes Trump’s performance in their first debate as “dire,” the reality is that in the opening minutes, he relentlessly hammered away on trade, the loss of manufacturing jobs and her shifting positions on the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal. And in a different context, she herself cites data showing that voters under economic stress were more negative toward immigration.

Clinton fell short in communicating a persuasive economic message of her own. She criticizes Joe Biden for saying this and notes that he campaigned across the Midwest and “talked plenty about the economy.” But his commitment was not in doubt; hers was. He was not the candidate; she was.

The tragedy here is that Clinton had an economic program that should have appealed to precisely the places she had to win.

The tragedy here is that she had, as she notes, an economic program that should have appealed to precisely the places she had to win: “massive infrastructure...new incentives to attract and support manufacturing jobs in hard hit communities...debt-free college.” It was on her website, but who among the undecided or wavering voters bothered to read it? She insists that on the campaign trail, she talked more about the economy and jobs than anything else—and cites a word frequency chart to prove it.

As T. S. Eliot wrote, “Between the idea and the reality.... Falls the shadow.” The shadow for Clinton is that what counts is not what you say but what people hear. Still, the failure to convey an economic message was not just her fault. The U.C.L.A. political scientist Lynn Vavreck found that from Oct. 8 on, “only 6 percent” of news coverage mentioned Clinton “alongside jobs or the economy.” (Only 10 percent mentioned Trump in that context, but arguably his economic message had long since broken through.) Clinton did have another means to deliver her message, paid advertising, but Vavreck calculated that only 9 percent of her television spots were about jobs or the economy. Instead three-quarters of her ads focused on leadership “traits” or character, frequently in the form of assaults on Trump.

Clinton observes that the “Access Hollywood” tape where Trump bragged about groping women was “a catastrophe” for his campaign. In fact, it may have been a catastrophe for hers: It became a mesmerizing, bright shiny object, and her television ads, the primary vehicle to get an economic message across, endlessly recounted her opponent’s gross misconduct. Even her slogan, “Stronger Together,” seems more about him than her—or as she puts it, the slogan highlighted that he was “risky” and “divisive.”

Trump would have been vulnerable to an economic assault. As Obama did with Mitt Romney in 2012, Clinton’s ads could have spotlighted his controversial business dealings and mistreatment of ordinary workers; then they could have moved on to arraign his proposed tax cuts for the wealthy and to convey Clinton’s plans on jobs, manufacturing and infrastructure. The strategy might not have been a silver bullet, but it could and probably would have been enough to move those 38,000 votes.

The Clinton campaign did not know the trouble it was in at the end because it relied so heavily on data analytics.

Finally, speaking of silver bullets, the Clinton campaign did not know the trouble it was in at the end because it relied so heavily on data analytics and in the last three weeks did not conduct telephone polls in the battleground states. Data analytics came into its own politically in Obama’s 2008 and 2012 campaigns; it is value added, but it is not the be-all and end-all in gauging the state of a race. If the assumptions are off, if past history is not prologue, data analytics can offer comfort that you are winning a Michigan or Wisconsin when you are not—which is exactly what happened here. Stan Greenberg, Bill Clinton’s pollster in 1992, calls the decision not to poll the battleground states in the closing weeks “malpractice and arrogance.”

We now know that the fake news, the Russian interference and the Facebook and Twitter bots were even more pervasive and poisonous than Hillary Clinton realized when she finished this book. We are living with a reckless, divisive, unstable, race-baiting and warmongering president, the worst in our history, someone who debases the office and could threaten our democracy or trigger a nuclear holocaust.

What Happened convinces me that Clinton would have been an excellent president, and not just in comparison with Trump. It also lays bare her shortcomings as a politician and reveals, probably as much as she possibly can, her post-election traumas. And between the lines, there is a sense that victory could have cooled her defensive reflexes and brought us a President Clinton who was not only competent but more comfortable in her own skin.

Maybe not—and of course, we will never know. But given the menacing fiasco of President Trump, this well-crafted book is in the end as painful to read as it must have been to write. At a human level, What Happened is poignant, too. Years after he lost 49 states, Walter Mondale asked George McGovern, who had been buried in a comparable landslide, when it stopped hurting. “Never,” McGovern replied. So it is for Hillary Clinton, who stumbled against the unelectable opponent and yet came so close. Whatever her mistakes, she deserved better than she got—and so did the country.

This article also appeared in print, under the headline “How Did She Lose?,” in the November 13, 2017, issue.